Breadcrumb

- Home

- Recent news stories

- K-State research details herbicide options for wheat growers to manage feral rye

Vipan Kumar, a weed scientist with Kansas State University, started hearing about feral rye concerns in central Kansas wheat fields from the day he arrived at the Agricultural Research Center in Hays in 2017. Four years later, he is completing a three-year research project studying this weed and how Kansas growers can take advantage of newer herbicide and varietal options to keep rye in their whiskey and out of their wheat fields.

“Feral or volunteer rye is a troublesome winter annual grass weed species in Kansas,” said Kumar, K-State assistant professor of weed science, in his research proposal. “The presence of feral rye may result in dockage and other losses in wheat quality.”

Kumar’s research was supported by the Kansas Wheat Commission, the Kansas Wheat Alliance and the Kansas Crop Improvement Association. The project details the biology and management of feral rye, downy brome and jointed goat grass in Kansas wheat production. A specific focus was the effectiveness of Aggressor (quizalofop-p-ethyl) herbicide on controlling feral rye and other weed species in wheat fields planted to quizalofop-resistant wheat varieties (CoAXium Wheat Production Systems).

“The ultimate goal of this project is to improve the sustainability and economic viability of Kansas wheat production by developing cost-effective management strategies for winter annual grassy weeds,” the proposal stated.

Feral rye is tricky to control, partly because its growth cycle mirrors wheat. Kumar and his team evaluated germination rates of feral rye on different temperatures, helping researchers better understand how the weed develops and when herbicide applications would be the most effective.

“It pretty much matches with what wheat requires in terms of germination,” Kumar said. “Feral rye has the same growth cycle winter wheat has. When we plant our wheat in September or October, that is the time it can start coming. Just along with the wheat, it vernalizes and goes dormant and then greens up in the spring.”

The presence of feral rye in a wheat field, however, causes several problems. Previous research indicated the economic threshold for feral rye is five to six plants per square yard. At that mark, up to 14 percent yield reduction has been observed in northeastern Colorado. Furthermore, contamination with feral rye seed increases wheat dockage and reduces the milling and baking characteristics of wheat flour.

And feral rye is a persistent pest that does not disappear after a single growing season.

“Feral rye seeds have very low dormancy,” Kumar said. “A single plant can produce 600 seeds, according to the literature. Less than one percent of those seeds are dormant and can be persistent in the soil. So, seed bank management is very important if you are going to look for long-term management of feral rye in your field.”

Kumar also observed wheat growers did not have effective herbicide options for feral rye control. Growers with rye issues often tried using the Clearfield wheat system, which combines the use of Beyond (imazamox) herbicide with a winter wheat cultivar containing the gene that corners tolerance to this herbicide. While effective for several annual grass and broadleaf weed species, growers reported mixed results for feral rye without clear markers of successful timing or rates.

But a newer herbicide-wheat varietal system from Colorado State University sparked Kumar’s interest. CoAXium wheat is herbicide-tolerant wheat that contains the AXigen trait, which has resistance to a different class of herbicides — namely Aggressor (quizalofop-p-ethyl).

Kumar decided to put both herbicides to the test. Starting in 2019, his team collected feral rye samples from 40 to 50 different fields, tricky but necessary to do at wheat harvest.

“We went to go and collect some of those feral rye survivors in the field at the time of wheat harvest because feral rye retains most of its seed at harvest,” Kumar said. “It doesn’t shatter, and it’s taller than wheat, so you can easily see from the road that this field has an issue, and this other field doesn’t have an issue.”

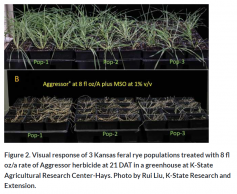

Kumar brought collected feral rye lines to the greenhouses in Hays and started screening them. Several feral rye populations were collected and tested using different rates of Beyond and Aggressor — at, below and above the recommended application rates. In the study, feral rye was completely killed with a field-use rate (8 fluid ounces per acre) of Aggressor plus an adjuvant at 21 days after treatment.

“What we found here in our greenhouse conditions is that our populations are very sensitive to Aggressor, which is a relatively new chemistry for wheat folks,” Kumar said. “But there were a lot more troubles with Beyond, as the majority of those populations had survivors in the greenhouse test.”

“Normally, the recommendation is eight ounces in the fall, followed by eight ounces in the spring — two applications will clean up your field,” Kumar said. “But, for feral rye, we have seen that eight ounces are not enough. You have to go with 10 to 12 ounces per acre in each application.”

Kumar also recommended using adjuvants with Aggressor to help with better absorption of the herbicide by the plant, including a non-ionic surfactant (NIS) in the fall and methylated seed oil (MSO) surfactant in the spring.

“The adjuvant helps to correct hard water issues as well as help in spreading out the herbicide molecules on the surface of those wheat plants,” he said. “It also helps that herbicide to penetrate into the plant.”

Timing is also important. Kumar emphasized waiting to spray in the fall until wheat is at the three-to-four leaf stage, where other winter annual grasses are growing as well. Then, in the spring, he cautioned growers to wait until full green-up for a spring application.

“You have to be careful. If those plants are dormant, this herbicide will only kill actively growing plants,” Kumar said. “So, we have to wait for our downy brome or feral rye or other grasses to become green and actively growing. Then we should apply our aggressive treatment in the spring. Otherwise, spraying too soon can result in escapes.”

Finally, a word of caution. Aggressor is not appropriate for all wheat varieties. Kumar pointed out graduate student work from Oklahoma State University that showed a 90 percent loss when Aggressor was applied to non-resistant wheat varieties. Remember, Beyond and Aggressor are two separate classes of herbicides, so not even Clearfield wheat will tolerate an application of Aggressor.

Kansas growers do, however, have access to nearly a dozen varieties of hard red winter (HRW) wheat lines that are part of the CoAXium wheat production system, meaning they are resistant to Aggressor. These varieties are not as high-yielding as other HRW varieties, but K-State researchers are introducing the same tolerance genes — which originated from Colorado State University — into higher-yielding germplasm best suited for Kansas growers.

Overall, the right combination of variety, herbicide, timing and rate can pay off for Kansas wheat growers — both for controlling a tricky weed and regaining yield.

“If you have an effective treatment in the fall or spring, we’ve seen 17 to 20 percent yield benefit with split applications in the fall and spring by controlling heavily infested feral rye in wheat,” Kumar said.

Learn more about the feral rye management research project at https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/article_new/management-of-feral-rye-with-coaxium-wheat-production-system-in-kansas-357.

###

Written by Julia Debes for Kansas Wheat